Semantic search engines comparison, Part 1 - ChromaDB, Elasticsearch and PostgreSQL

When I wrote the last post I realized I didn’t know much about how modern similarity search engines work. It’s time to rectify that. In this three-part series, I’ll explore two modern vector databases used for semantic search and two “classic” engines that have been updated in recent years to handle this scenario more effectively. These engines are ChromaDB, Milvus, Elasticsearch, and PostgreSQL. I’ll talk about Milvus in the last post, as it needs to run under a Linux environment and emulating that with Docker gives me a lot of headache - I didn’t take my Linux machine with me on this Christmas break. I won’t really go into any details describing the other features (like hybrid search), as I only want to focus on a single one - semantic search.

Side note: I’m aware of Pinecone, however, in this series I wanted to focus either on something I already know (classic relational DB, Elasticsearch) or on novelties that seemed to be simple enough (ChromaDB, Milvus). I’ll probably get to Pinecone eventually in another post.

Requirements

- Compare the engines functionally - how easy it is to index and query them, how many configuration is required to set up the indexes etc.

- Check out the offered optimization methods

Side note: I will cover optimization in the next post and Milvus in the one after that.

The code

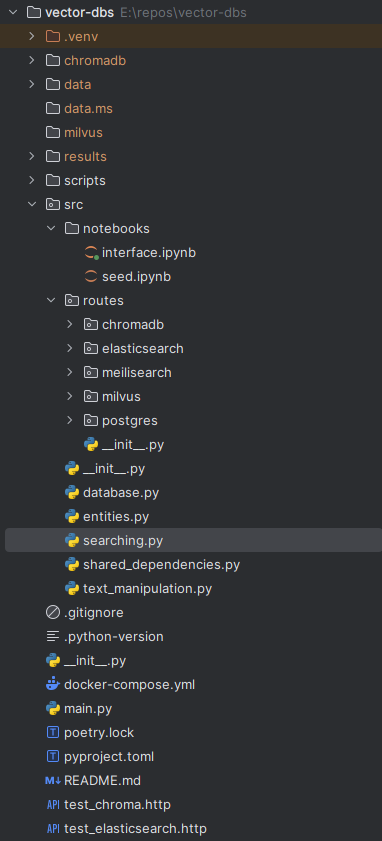

For this experiment I generated FastAPI backend and created some Jupyter Notebooks. I might have as well just done everything in Jupyter Notebooks, but I also wanted to refresh my FastAPI knowledge, and using this framework doesn’t really complicate things. Below you’ll find a screenshot of the project layout:

I’ll go into details of each route in the section dedicated to that route but first I’d like to create a general overview. Even though Elasticsearch and Postgres (with the pgml extension) offer ways to generate embeddings on the fly, I decided not to use that option. The reason is simple - configuration. With the pgml extension there’s a way to configure the database to use GPU, but I didn’t want to get buried in the configuration. For Elasticsearch I couldn’t really find anything similar. ChromaDB and Milvus on the other hand are GPU-native.

Notebooks

As shown in the screenshot above, the src folder contains several notebooks. The one named seed downloads data from kagglehub. The data comes from two sources: a list of news articles and abstracts of scientific articles. The code is fairly straightforward:

import chardet

import kagglehub

import os

import pandas as pd

from pony.orm import db_session, commit

from src.database import db

from src.entities import Article

db.generate_mapping(create_tables=True)

news_articles_path = kagglehub.dataset_download("asad1m9a9h6mood/news-articles")

research_articles_path = path = kagglehub.dataset_download("arashnic/urban-sound")

def convert_file_encoding(file_path: str, original_encoding: str, target_encoding: str) -> None:

with open(file_path, "r", encoding=original_encoding) as file:

content = file.read()

with open(file_path, "w", encoding=target_encoding) as file:

file.write(content)

def get_dataframe(path: str) -> pd.DataFrame:

csv_files = [f for f in os.listdir(path) if f.endswith(".csv")]

dfs = []

for file in csv_files:

with open(os.path.join(path, file), "rb") as rawdata:

result = chardet.detect(rawdata.read(100000))

encoding = result["encoding"]

convert_file_encoding(os.path.join(path, file), encoding, "utf-8")

dfs.append(pd.read_csv(os.path.join(path, file), encoding="utf-8"))

combined = pd.concat(dfs)

return combined

with db_session:

for index, row in news_dataframe.iterrows():

Article(

title=row["Heading"],

txt=row["Article"]

)

commit()

for index, row in research_dataframe.iterrows():

Article(

title=row["TITLE"],

txt=row["ABSTRACT"]

)

commit()

The other one contains code that I created to make it easier to interact with the api. Even though FastAPI generates OpenAPI docs that are usable on their own, and PyCharm generated those test_*.http files, nothing beats a proper interface, more so when it’s so easy to create:

import itertools

import time

import pandas as pd

import requests

from IPython.core.display_functions import clear_output

from ipywidgets import widgets, HTML

search_engine_box = widgets.Dropdown(

options=["chroma", "elasticsearch", "postgres"],

value="chroma",

description="Pick the search engine:",

disabled=False,

)

model_box = widgets.Dropdown(

options=["all-mpnet-base-v2", "multi-qa-mpnet-base-cos-v1"],

value="all-mpnet-base-v2",

description="Pick the model type:",

disabled=False,

)

text_input = widgets.Text(

value="",

placeholder="Enter query",

description="Enter query:",

disabled=False,

)

submit = widgets.Button(

description="Submit",

button_style="success",

)

time_label = widgets.Label(

value="Request time: -- s",

layout={'margin': '10px 0px 10px 0px'}

)

results_output = widgets.Output()

def render_results(data):

results_html = ""

for item in data:

doc_id = item.get("id", "N/A")

distance = item.get("distance", "N/A")

similarities = item.get("similarities", [])

results_html += f"""

<div style='border: 1px solid #ccc; padding: 10px; margin: 10px 0; border-radius: 5px;'>

<strong>Doc ID:</strong> {doc_id}<br>

<strong>Distance:</strong> {distance:.4f}<br>

<hr>

"""

for sim in similarities:

text, score, strength = sim

color = dict(weak="red", mid="yellow", strong="green").get(strength, "black")

results_html += f"""

<p style='color: {color}; margin: 5px 0;'>

{text} (score: {score:.4f}, strength: {strength})

</p>

"""

results_html += "</div>"

return HTML(results_html)

def run_request(engine: str, model: str, query: str, model_suffix: str = "") -> tuple[str, int]:

start_time = time.time()

response = requests.get(

f"http://127.0.0.1:8000/api/v1/{engine}/search/{model}{model_suffix}?query_string={query}"

)

end_time = time.time()

elapsed_time = end_time - start_time

response_data = response.json()

return response_data, elapsed_time

def on_button_clicked(b: widgets.Button):

with results_output:

clear_output()

selected_engine = search_engine_box.value

selected_model = model_box.value

query_string = text_input.value

response_data, elapsed_time = run_request(selected_engine, selected_model, query_string)

time_label.value = f"Request time: {elapsed_time:.4f} s"

display(render_results(response_data))

submit.on_click(on_button_clicked)

display(search_engine_box, model_box, text_input, submit, time_label, results_output)

This is the first part of the notebook. Its goal is to display a set of controls that allow me to select the engine, model variation, and input a query to send to the backend. The most interesting part here is the render_results function. If you examine it closely, you’ll notice that I’m coloring parts of the text differently based on how they were tagged by the backend. The backend assigns three labels to text segments: strong, mid, and weak. These labels correspond to green, yellow, and red highlights in the interface. I didn’t just want to retrieve the documents most similar to the query string - I also wanted to see which parts of the text were the most relevant.

This notebook also contains a part dedicated to measuring the performance of each engine+model combination but that will be a part of the next post.

Common code

Now let’s dive into the shared components of this project starting with entities:

from pony.orm import Required, Optional, Set

from .database import db

class Article(db.Entity):

title = Required(str, max_len=1024)

txt = Required(str)

all_mpnet_embeddings_halfvec = Set("ArticleEmbeddingAllMpnetBaseV2Halfvec")

multi_qa_mpnet_embeddings_halfvec = Set("ArticleEmbeddingMultiQaMpnetBaseCosV1Halfvec")

class ArticleEmbeddingAllMpnetBaseV2(db.Entity):

article = Required(Article)

sentences = Required(str, max_len=8192)

embedding = Optional(str, sql_type="vector(768)")

class ArticleEmbeddingMultiQaMpnetBaseCosV1(db.Entity):

article = Required(Article)

sentences = Required(str, max_len=8192)

embedding = Optional(str, sql_type="vector(768)")

class ArticleEmbeddingAllMpnetBaseV2Halfvec(db.Entity):

article = Required(Article)

sentences = Required(str, max_len=8192)

embedding = Optional(str, sql_type="halfvec(768)")

class ArticleEmbeddingMultiQaMpnetBaseCosV1Halfvec(db.Entity):

article = Required(Article)

sentences = Required(str, max_len=8192)

embedding = Optional(str, sql_type="halfvec(768)")

I really like Ponyorm. I haven’t used it in a commercial project yet because usually the team would choose the more popular option, which is SQLAlchemy but since this one is a non-commercial one, I can pick whatever I want and I decided that pony will make my life easier. When I started learning Python some 16 years ago I kept hearing the term “idiomatic python” everywhere, maybe this is why I like pony so much - in the simple case it allows us to write code that will select data from the db as if it was a standard Python collection. It looks pretty and I deserve pretty things :)

And so, above you can see a standard ponyorm entity definitions with one twist - it doesn’t natively support the vector type (but that’s not an issue, vectors will only be used on the database level, not in python). Of these three entities only the first one is “shared” - it was used in the seed notebook to populate the set of articles. The other ones will come into play in the post about performance.

Now let’s talk about the text_manipulation.py file starting with the contained chunk_text function and the accompanying _ensure_punkt_downloaded one:

from functools import singledispatch

from typing import Iterable

import nltk

from nltk.tokenize import sent_tokenize

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

from transformers import MPNetTokenizerFast

def chunk_text(text: str, tokenizer: MPNetTokenizerFast) -> Iterable[str]:

"""

Splits text into chunks that respect the model's token limit,

grouping sentences together when possible.

"""

_ensure_punkt_downloaded()

sentences = sent_tokenize(text)

current_chunk = []

current_tokens = 0

chunks = []

for sentence in sentences:

"""

Side note, the below would generate:

Token indices sequence length is longer than the specified maximum sequence length for this model (1127 > 384).

Running this sequence through the model will result in indexing errors

If it was called on full text.

"""

sentence_tokens = tokenizer.tokenize(sentence)

sentence_token_count = len(sentence_tokens)

if current_tokens + sentence_token_count > tokenizer.model_max_length:

if current_chunk:

chunk_text = tokenizer.convert_tokens_to_string(tokenizer.tokenize(" ".join(current_chunk)))

chunks.append(chunk_text)

current_chunk = [sentence]

current_tokens = sentence_token_count

else:

current_chunk.append(sentence)

current_tokens += sentence_token_count

if current_chunk:

chunk_text = tokenizer.convert_tokens_to_string(tokenizer.tokenize(" ".join(current_chunk)))

chunks.append(chunk_text)

return chunks

def _ensure_punkt_downloaded():

"""

NLTK - punkt is capable of splitting text into sentences based on punctuation, capitalization, and

linguistic patterns which will come in handy to properly split the texts.

"""

try:

nltk.data.find("tokenizers/punkt")

nltk.data.find("tokenizers/punkt_tab")

except LookupError:

print("Downloading 'punkt' tokenizer...")

nltk.download("punkt")

nltk.download("punkt_tab")

print("'punkt' has been successfully downloaded.")

Transformers (or any NLP models, really) can only process chunks of text. Remember the semantic vectors from the last post? In reality, these are vectors that encapsulate meaning within those chunks. The sentence transformer models I selected use a context window of 384 tokens. Very long chunks of text would inevitably exceed this token limit, which is why splitting is necessary.

The first step in this code is calling the _ensure_punkt_downloaded function to download the necessary nltk toolkit components for proper text splitting. However, it’s not perfect. Sometimes it splits every sentence; other times, it leaves clusters of sentences intact. I suspect this inconsistency is due to the data downloaded by the seed notebook. In particular, the article contents are not very clean, and even I had difficulty identifying clear splitting points while reading through them. Additionally, the presence of HTML-like artifacts in the text doesn’t help.

Once the text is initially tokenized (in the nltk sense, not in the transformer sense - these are two very different tokenization processes), a loop runs to perform transformer-level tokenization on the chunks. In the end, the tokens are glued together to form sentences.

Why do it this way? Well, it’s the model’s responsibility to tokenize and encode the sentences. You can see this in the sentence_transformers source code (file: SentenceTransformer.py, lines 576 or 591, as of December 28, 2024). However, for the model to tokenize and encode effectively for semantic search, I first need to provide it with chunks of text it can properly process. That’s why this preprocessing step is essential.

The last function in this file is tag:

@singledispatch

def tag(data):

raise NotImplementedError

@tag.register(str)

def _(

query: str,

contents: list[str],

model: SentenceTransformer

) -> Iterable[tuple[str, float, str]]:

encoded_query = model.encode(query)

encoded_sentences = model.encode(contents)

similarities = model.similarity(encoded_query, encoded_sentences)

labeled_results = []

for chunk, similarity in zip(contents, similarities.tolist()[0]):

label = tag(similarity)

labeled_results.append((chunk, similarity, label))

return labeled_results

@tag.register(float)

def _(similarity: float) -> str:

if similarity > .6:

return "strong"

elif similarity >= .3:

return "mid"

else:

return "weak"

Side note: I’m implementing a poor man’s version function overloading - singledispatch decorator allows function behavior to change based on the type of the first argument.

As you might have already guessed, this is the piece of code responsible for tagging the sentences after the search is performed. There’s one important but not immediately visible detail here. There are a few methods of calculating vector similarity: l2, euclidean distance and cosine similarity. The sentence transformer models I picked use the last one as the default, so when I run model.similarity, a cosine similarity is being calculated. It’s very important to use the same metric on the vector storage level, otherwise the numbers returned from the database and the ones obtained in python will differ.

As for the shared_dependencies.py file, it contains functions that are used by every route:

from pony.orm.core import DBSessionContextManager, db_session

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

_base_model: SentenceTransformer | None = None

_alt_model: SentenceTransformer | None = None

def get_explicit_default_transformer() -> SentenceTransformer:

return SentenceTransformer("all-MiniLM-L6-v2")

def get_all_mpnet_base_v2_transformer() -> SentenceTransformer:

global _base_model

if _base_model is None:

_base_model = SentenceTransformer("all-mpnet-base-v2")

return _base_model

def get_multi_qa_mpnet_base_cos_v1_transformer() -> SentenceTransformer:

global _alt_model

if _alt_model is None:

_alt_model = SentenceTransformer("multi-qa-mpnet-base-cos-v1")

return _alt_model

def get_db_session() -> DBSessionContextManager:

return db_session

As you can see, these function implement a singleton pattern. That’s quite important from the performance standpoint, as creation of a SentenceTransformer class each time it’s requested takes time and allocated more and more GPU memory.

The all-MiniLM-L6-v2 sentence transformer is the one ChromaDB driver would use to vectorized the passed in texts by default. I’m not using it though. I’m using the two other ones. all-mpnet-base-v2 is a decent one, and they say this on the sentence transformers page:

The all-mpnet-base-v2 model provides the best quality

The choice of the other one was a semi-random one. I just needed another model to compare the results both in terms of performance and search results relevancy. In this case the vectors obtained from multi-qa-mpnet-base-cos-v1 do a better job in the second case.

ChromaDB

The pattern you’ll notice in each route is that there are two functions for indexing the data, defined like this:

@chroma_router.post("/vectorize/all-mpnet-base-v2")

async def vectorize_using_all_mpnet_base_v2_transformer(

db_session: DBSessionContextManager = Depends(get_db_session),

client_coroutine: Coroutine[Any, Any, chromadb.AsyncClientAPI] = Depends(get_chroma_client),

model: SentenceTransformer = Depends(get_all_mpnet_base_v2_transformer)

) -> None:

client = await client_coroutine

await _vectorize_with(db_session, client, model, GENERAL_PURPOSE_COL)

@chroma_router.post("/vectorize/multi-qa-mpnet-base-cos-v1")

async def vectorize_using_multi_qa_cos_v1_transformer(

db_session: DBSessionContextManager = Depends(get_db_session),

client_coroutine: Coroutine[Any, Any, chromadb.AsyncClientAPI] = Depends(get_chroma_client),

model: SentenceTransformer = Depends(get_multi_qa_mpnet_base_cos_v1_transformer)

) -> None:

client = await client_coroutine

await _vectorize_with(db_session, client, model, SEMANTIC_SEARCH_COL)

And two other ones that are used for searching:

@chroma_router.get("/search/all-mpnet-base-v2", response_model=Iterable[SearchResult])

async def all_mpnet_base_v2_search(

query_string: str,

db_session: DBSessionContextManager = Depends(get_db_session),

client_coroutine: Coroutine[Any, Any, chromadb.AsyncClientAPI] = Depends(get_chroma_client),

model: SentenceTransformer = Depends(get_all_mpnet_base_v2_transformer)

) -> Iterable[SearchResult]:

client = await client_coroutine

return await _search(query_string, db_session, client, model, GENERAL_PURPOSE_COL)

@chroma_router.get("/search/multi-qa-mpnet-base-cos-v1", response_model=Iterable[SearchResult])

async def multi_qa_mpnet_base_cos_v1_search(

query_string: str,

db_session: DBSessionContextManager = Depends(get_db_session),

client_coroutine: Coroutine[Any, Any, chromadb.AsyncClientAPI] = Depends(get_chroma_client),

model: SentenceTransformer = Depends(get_multi_qa_mpnet_base_cos_v1_transformer)

) -> Iterable[SearchResult]:

client = await client_coroutine

return await _search(query_string, db_session, client, model, SEMANTIC_SEARCH_COL)

However, the corresponding _vectorize and _search functions are very different. Let’s start by looking at the chromadb vectorization function:

async def _vectorize_with(

db_session: DBSessionContextManager,

client: chromadb.AsyncClientAPI,

model: SentenceTransformer,

collection: str

) -> None:

try:

await client.get_collection(collection)

await client.delete_collection(collection)

except Exception as exc:

print(exc)

collection = await client.create_collection(collection, metadata={"hnsw:space": "cosine"})

tokenizer = model.tokenizer

with db_session:

all_items = [item for item in select(x for x in Article)]

ids = []

docs = []

metadatas = []

embeddings = []

for item in all_items:

chunks = chunk_text(item.txt, tokenizer)

for chunk_number, chunk in enumerate(chunks):

chunk_id = f"{item.id}-chunk-{chunk_number}"

embedding = model.encode(chunk)

ids.append(chunk_id)

docs.append(chunk)

metadatas.append({"name": item.title, "chunk_number": chunk_number})

embeddings.append(embedding.tolist())

chunk_size = 2048

workers = []

for ids_chunk, docs_chunk, metadatas_chunk, embeddings_chunk in zip(

_chunkify(ids, chunk_size),

_chunkify(docs, chunk_size),

_chunkify(metadatas, chunk_size),

_chunkify(embeddings, chunk_size)

):

workers.append(

collection.add(

documents=docs_chunk,

metadatas=metadatas_chunk,

ids=ids_chunk,

embeddings=embeddings_chunk

)

)

await asyncio.gather(*workers)

Each time it runs, it recreates chroma collections. By default chroma uses l2 distance calculation (I think), so I needed to set the hnsw:space parameter to cosine explicitly, otherwise the distance numbers returned from chroma didn’t correspond to the ones obtained by running model.similarity method. After the collection is created this code splits article texts into smaller chunks, so that they can be properly tokenized and encoded. The last lines initialize ChromaDB indexing.

Side note: you don’t have to pass in embeddings directly like that. You can use chroma defaults in which case you’d only pass documents to the collection.add call. Chroma driver would then internally encode the document. It may not be enough though, because the default model it uses is all-MiniLM-L6-v2 and there are better (and slower) ones.

The _search function is a little bit shorter:

async def _search(

query_string: str,

db_session: DBSessionContextManager,

client: chromadb.AsyncClientAPI,

model: SentenceTransformer,

collection: str

) -> Iterable[SearchResult]:

collection = await client.get_or_create_collection(collection)

query_vector = model.encode(query_string or "")

results = await collection.query(query_embeddings=query_vector)

id_to_doc_map = _initialize_map(results)

with db_session:

matching_articles = select(a for a in Article if a.id in id_to_doc_map.keys())[:]

update_map(id_to_doc_map, matching_articles, model, query_string)

return id_to_doc_map.values()

There’s no point in showing what the _initialize_map and update_map function do, as it would only make this post longer (and it’s pretty long already). There’s no magic happening inside them, just value assignment. Besides, I will show what the search endpoints return at the end of this post and it will all become clear. The most important things happen in the attached code which is: getting a collection, encoding the query, and getting the data.

I can sum up my ChromaDB interaction in a single word: simplicity. This was the first piece of tech I started checking out for this post and glueing all the pieces together was very easy and obvious. However, one needs to remember that it’s still a new product and it’s missing some features you may want to have on production. I think their version number is somewhere around 0.6.0. For this post I used chroma with only a single, local node, but their documentation mentions AWS/GCP/Azure deployment options. I haven’t tried that, but I glanced over the AWS Cloud Formation template they provide and it looks like it’s a single node one. Obviously, you could deploy it to multiple EC2 instances, the thing is, all of them would have repeated data, you’d have to juggle their IPs, and you’d have to configure them all manually. I’m missing some cluster management tools here…

Side note: I just noticed ChromaDB team is preparing a cloud solution which is cool, obviously. However, I would be even happier if they allowed for an on-prem version of their software. Many people consider cloud a scam aiming to drain them of their money, and quite often they are right…

Elasticsearch

The second candidate is a classic one, and since its name includes the word “search,” no article comparing search engines would be complete without mentioning it. Elasticsearch has been a staple in the search engine landscape for years. I first used it over 13 years ago as a backend for the search functionality of the Polish Football Association Organization. Since then, the website has undergone at least two rebrandings that I’m aware of, along with possible deep technical changes - perhaps they even moved away from Elasticsearch entirely.

After that, I mostly encountered Elasticsearch as part of the ELK stack. In one project, I recommended using it for full-text search, but we ultimately chose MongoDB. At the time, MongoDB’s optimizations outperformed Elasticsearch in terms of speed.

Nowadays Elasticsearch team is doing what the rest of the world is doing - adopting semantic search-related tools to make their product better. They introduced the dense_vector field type somewhere around version 7.3 of the product and that enabled true semantic search functionality to be implemented using ES as the backend. However, it wasn’t half bad in the early days anyway. Before the dense_vector they used (and still do; there are many ES searching flavors) a combination of term-based and keyword-based matching techniques using the so called inverted indices (they map each unique term in the dataset to a list of documents containing that term, that way only that small, unique list needs to be scanned). They also used algorithms like TF-IDF (it’s also prevalent in many machine learning tutorials showing simple sklearn concepts), synonym dictionaries, stemming and lemmatization to transform and enrich incoming text so that their database would be able to find more relevant results. To me it was quite impressive that after some tweaking you would have a Google-like search engine embedded into your server app. Could it even get better?

Well, it got better and simpler with the inception of dense_vector and all the stuff around it. The classic ES search capabilities suffered from lack of contextual understanding, so if you didn’t use the set of words ES used to index a given document, you wouldn’t see it on the result list. dense_vector allows ES to implement an actual semantic search engine.

The main routes for vectorization and search look mostly the same as in the ChromaDB case. One difference is that I added endpoints for vectorization with quantization turned on, but they look the same anyway. Let’s dive straight into the vectorization function:

async def _vectorize_with(

db_session: DBSessionContextManager,

client: AsyncElasticsearch,

model: SentenceTransformer,

index: str,

quantize: bool = False

) -> None:

if await client.indices.exists(index=index):

await client.indices.delete(index=index)

tokenizer = model.tokenizer

if quantize:

more_options = dict(index_options=dict(type="int4_hnsw"))

else:

more_options = dict(index_options=dict(type="hnsw"))

es_index = dict(

mappings=dict(

properties=dict(

body=dict(type="text"),

body_vector=dict(

type="dense_vector",

dims=model.get_sentence_embedding_dimension(),

index=True,

similarity="cosine",

**more_options

),

doc_id=dict(type="integer"),

)

)

)

await client.indices.create(index=index, body=es_index)

with db_session:

all_items = [item for item in select(x for x in Article)]

chunk_size = 500

for i in range(0, len(all_items), chunk_size):

items = all_items[i:i + chunk_size]

bulk_data = []

for item in items:

_id = item.id

chunks = chunk_text(item.txt, tokenizer)

for chunk_number, chunk in enumerate(chunks):

chunk_id = f"{_id}-chunk-{chunk_number}"

embedding = model.encode(chunk).tolist()

bulk_data.append(dict(

_index=index,

_id=chunk_id,

_source=dict(

body=chunk,

body_vector=embedding,

doc_id=int(_id)

)

))

try:

await helpers.async_bulk(client, bulk_data)

except helpers.BulkIndexError as e:

print("Bulk index error occurred!")

for error in e.errors:

print(error)

raise e

Side note: there’s an error here. I remember reading ponyorm docs saying it doesn’t play nicely with async code, like the one shown here, and gave an example that looked similar in structure to this one. Why is it like this then? Well, in its first version I didn’t use AsyncElasticsearch class but its sync twin - all the code was sync. Then I just switched the implementation, but I tested it only by using the search endpoints; their code is shaped differently and it works with async/await. I didn’t run the vectorization process because it takes time.

Three things here:

- I’ll talk about

int4_hnswin the next post. - If similarity argument isn’t set explicitly ES will use l2.

- They also offer the built-in embedding mechanisms. Given the fact that ES can be deployed in a cluster, thus the embedding process can be offloaded to the database itself, that might be the smarter move in production code (because the server app wouldn’t be the bottleneck), but here, embedding on the server is good enough.

As for the search function, I only put it here as a context. The real interesting part is in the _initialize_map function:

async def _search(

query_string: str,

db_session: DBSessionContextManager,

client: AsyncElasticsearch,

model: SentenceTransformer,

index: str

) -> Iterable[SearchResult]:

query_embedding = model.encode(query_string)

results = await client.search(

index=index,

knn=dict(

field="body_vector",

query_vector=query_embedding,

k=10,

num_candidates=100

)

)

id_to_doc_map = _initialize_map(results)

with db_session:

matching_articles = select(a for a in Article if a.id in id_to_doc_map.keys())[:]

update_map(id_to_doc_map, matching_articles, model, query_string)

return id_to_doc_map.values()

def _initialize_map(results: dict) -> dict[int, SearchResult]:

id_to_doc_map = {}

for row in results["hits"]["hits"]:

chunk_id = row["_id"]

entity_id = int(chunk_id.split("-")[0])

# dense vector docs: https://www.elastic.co/guide/en/elasticsearch/reference/current/dense-vector.html

# it says: "The document _score is computed as (1 + cosine(query, vector)) / 2"

# the below reverts the process

cosine_similarity = (2 * row["_score"]) - 1

distance = 1 - cosine_similarity

if entity_id not in id_to_doc_map:

id_to_doc_map[entity_id] = SearchResult(

distance=distance,

id=entity_id,

doc="",

similarities=[]

)

return id_to_doc_map

The _initialize_map function does one interesting thing - it inverts the score calculation performed by ES. Why do I do that? Because I want to be able to compare the numbers returned for the same documents from different backends.

Again, it’s quite simple. I didn’t really try to go into any depths to check how the similarity search process can be optimized on the engine level, but apart from using different embeddings, or HNSW indices (which ES does anyway), not much can be done. Just to make sure, I’ll look into that in my next post.

Postgresql

This database doesn’t really need an introduction. PostgreSQL has been flying high above the waves since its inception and when an interesting technology appeared in the data storage land, they were the first ones to put it to good use as part of their database (document databases vs jsonb column type for example). With AI and ML disrupting the IT industry, PGSQL authors don’t want to fall behind. The pgml extension is a microcosmos deserving a separate blog post, so I’ll leave it out of this one. However, for similarity search it’s not really needed. What is needed is the pgvector extension. If you read the Elasticsearch section, this will sound familiar, because the goal of both - dense_vector in ES and vector in PG is the same - to store long vectors to be used by similarity algorithms.

Differently from Elasticsearch, it needs to be installed before it’s used:

postgres:

image: pgvector/pgvector:0.8.0-pg16

environment:

- POSTGRES_USER=vectors

- POSTGRES_PASSWORD=vectors

- POSTGRES_DB=vectors

- POSTGRES_HOST_AUTH_METHOD=trust

ports:

- "5435:5432"

volumes:

- vec_postgres_data:/var/lib/postgresql/data

- ./scripts:/docker-entrypoint-initdb.d

And this is what the activation sql script contains:

CREATE EXTENSION IF NOT EXISTS vector;

Remember the ArticleEmbeddingAllMpnetBaseV2 and ArticleEmbeddingMultiQaMpnetBaseCosV1 entities from the beginning of this post? They were defined there to be used in Postgres. In ChromaDB there were collections, Elasticsearch has indices and databases have database tables :) Vectorization code looks similar to the one you saw before:

def _vectorize_with(

db_session: DBSessionContextManager,

model: SentenceTransformer,

entity_constructor: Callable[[Article, str, str], Any],

table_name: str,

halfvec: bool = False

) -> None:

tokenizer = model.tokenizer

with db_session:

if not halfvec:

db.execute(f"CREATE INDEX {table_name}_embedding_idx ON {table_name} USING hnsw (embedding vector_cosine_ops);")

else:

db.execute(

f"CREATE INDEX {table_name}_embedding_idx ON {table_name} USING hnsw (embedding halfvec_cosine_ops);")

all_item_ids = [item for item in select(x.id for x in Article)]

for batch in _chunk_list(all_item_ids, 100):

with db_session:

batch_items = select(x for x in Article if x.id in batch)[:]

for item in batch_items:

chunks = chunk_text(item.txt, tokenizer)

for chunk in chunks:

embedding = model.encode(chunk).tolist()

stringified_embedding = json.dumps(embedding)

entity_constructor(item, chunk, stringified_embedding)

The search function:

def _search(

db_session: DBSessionContextManager,

model: SentenceTransformer,

query_string: str,

table_name: str,

halve: bool = False

) -> Iterable[SearchResult]:

query_embedding = model.encode(query_string).tolist()

qembedding = json.dumps(query_embedding)

with db_session:

if halve:

db.execute("SET LOCAL hnsw.ef_search = 20;")

query = """

WITH best_articles AS (

SELECT ae.article AS article_id, MIN(ae.embedding <=> $qembedding) AS best_distance

FROM {table_name} ae

GROUP BY ae.article

ORDER BY best_distance ASC

LIMIT 10

)

SELECT

ba.article_id,

a.txt,

ba.best_distance,

ae.sentences,

(1 - (ae.embedding <=> $qembedding)) AS similarity

FROM {table_name} ae

JOIN best_articles ba ON ae.article = ba.article_id

INNER JOIN article a ON ae.article = a.id

ORDER BY ba.best_distance ASC, ae.article, similarity ASC;

""".format(table_name=table_name)

result = db.execute(query)

articles = {}

for article_id, txt, best_distance, sentence, similarity in result:

if article_id not in articles:

articles[article_id] = SearchResult(

id=article_id,

distance=best_distance,

doc=txt,

similarities=[]

)

articles[article_id].similarities.append((

sentence,

similarity,

tag(similarity)

))

return articles.values()

When writing the code for PostgreSQL, I realized something I had been doing subconsciously. In the other two cases, even though I saved the unembedded sentences alongside their vectors, those sentences were slightly transformed - they were the output of the tokenization and reconstruction process. Because of this, during searches, I avoided using them directly in the output phase and instead fetched the original article data from the database. This approach allowed me to present the interface with untouched data while still ensuring accurate similarity scores.

In the PostgreSQL case, I didn’t follow this pattern because I focused on crafting a single, large query. This query retrieves the top 10 text chunks (using a CTE) and then joins that data with the original article content. Finally, cosine similarity is calculated between the embedding and the user input (<=> operator represents cosine similarity).

One weird thing to note is the use of a query variable $qembedding that doesn’t seem to be set anywhere. If you go into PonyORM docs, you’ll find this section. That’s the weirdest thing I saw in Python, namely this part:

When Pony encounters such a parameter within the SQL query it gets the variable value from the current frame (from globals and locals) or from the dictionary which is passed as the second parameter.

“From the current frame”… Yep, they actually inspect the current stack trace to find a variable with a name corresponding to the one used in sql query. Obviously you don’t have to use that and be more explicit with the dict parameter, but it sounded so weird, I felt an internal pressure to use it.

I’d say PGSQL is a safe choice if you like to keep the data in one place. Sure, it’s so cool to use 20 different storages and surf the hype-wave each day, but maybe you’re building a small product, and you want to simplify your infrastructure as much as possible? If so, you probably use some kind of a relational database. Why not PG?

Summary

I’ve decided to wrap up this post here and cover the remaining topics in the next one. What’s left is to explore how each of the selected engines can be optimized, describe the Milvus integration, and compare their performance.