Bounding box detection for HAM10000 dataset with bigger model and CIoU loss function

There are many loss functions commonly used in the object detection space of AI. SmoothL1Loss is the simplest one. Beyond that, there is a gradient of the *IoU family. In this variation of my simple model, I decided to use the CIoU loss function, as it is regarded as the best one in the family.

The code

Bigger variation

If you read the previous post, you’ll notice that the only difference between the architecture used there and this one is that the conv2 and conv3 layers’ in_channels parameter has a higher value.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

class BoundingBoxModel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super(BoundingBoxModel, self).__init__()

self.conv1 = nn.Conv2d(3, 32, kernel_size=3, stride=1, padding=1)

self.conv2 = nn.Conv2d(32, 64, kernel_size=3, stride=1, padding=1)

self.conv3 = nn.Conv2d(64, 128, kernel_size=3, stride=1, padding=1)

self.pool = nn.MaxPool2d(kernel_size=2, stride=2, padding=0)

self.fc1 = self._initialize_fc1()

self.fc2 = nn.Linear(128, 4)

def forward(self, x: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

x = self._run_first_layers(x)

x = F.relu(self.fc1(x))

x = self.fc2(x)

return x

def _initialize_fc1(self) -> nn.Linear:

with torch.no_grad():

dummy_input = torch.zeros(1, 3, 150, 200)

x = self._run_first_layers(dummy_input)

input_size = x.size(1)

return nn.Linear(input_size, 128)

def _run_first_layers(self, x: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

x = self.pool(F.relu(self.conv1(x)))

x = self.pool(F.relu(self.conv2(x)))

x = self.pool(F.relu(self.conv3(x)))

x = torch.flatten(x, start_dim=1)

return x

SmoothL1Loss (Huber loss) formula and explanation

\[\begin{aligned} \text{SmoothL1Loss}(x, y) = \begin{cases} (x - y)^2 & \text{if } |x - y| < 1 \\ |x - y| & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \end{aligned}\]This function combines two widely known loss functions: MAE and MSE. It was used in the previous notebook, and is explained here, so that the comparison between it and the CIoU loss is easier. If the error is small, as given by the first branch of the formula, MSE is used; if it’s large, MAE is used. The main advantage of this function is that the use of MAE prevents very large prediction errors from disproportionately affecting the overall loss, which in extreme cases can greatly slow model convergence. The number \(1\) at the end of the first branch is a threshold parameter that can be adjusted, though the default is \(1\).

CIoU loss

The motivation for creating this loss function is that it is more specific to the problem at hand. I could have used the one that’s implemented in the torchvision.ops module but when learning something new and complex I usually try to implement it myself. First, the code:

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

def bbox_iou(

bboxes1: torch.Tensor,

bboxes2: torch.Tensor,

eps: float

) -> torch.Tensor:

"""

:param bboxes1: Expected to be already in transposed format -> (4, N)

:param bboxes2: Expected to be already in transposed format -> (4, N)

:param eps: Param for preventing zero-division errors

:return:

"""

b1_x1, b1_y1, b1_x2, b1_y2 = bboxes1

b2_x1, b2_y1, b2_x2, b2_y2 = bboxes2

inter_rect_x1 = torch.max(b1_x1, b2_x1)

inter_rect_y1 = torch.max(b1_y1, b2_y1)

inter_rect_x2 = torch.min(b1_x2, b2_x2)

inter_rect_y2 = torch.min(b1_y2, b2_y2)

inter_area = torch.clamp(inter_rect_x2 - inter_rect_x1, min=0) * torch.clamp(inter_rect_y2 - inter_rect_y1, min=0)

b1_area = (b1_x2 - b1_x1) * (b1_y2 - b1_y1)

b2_area = (b2_x2 - b2_x1) * (b2_y2 - b2_y1)

union_area = b1_area + b2_area - inter_area + eps

iou = inter_area / union_area

return iou

def bbox_ciou(

bboxes1: torch.Tensor,

bboxes2: torch.Tensor,

eps: float = 1e-7

) -> torch.Tensor:

"""

bboxes1, bboxes2 should be tensors of shape (N, 4), with each box in (x1, y1, x2, y2) format

"""

# transpose both to get xs and ys as vectors (below)

bboxes1 = bboxes1.t()

bboxes2 = bboxes2.t()

b1_x1, b1_y1, b1_x2, b1_y2 = bboxes1

b2_x1, b2_y1, b2_x2, b2_y2 = bboxes2

iou = bbox_iou(bboxes1, bboxes2, eps)

b1_center_x = (b1_x1 + b1_x2) / 2

b1_center_y = (b1_y1 + b1_y2) / 2

b2_center_x = (b2_x1 + b2_x2) / 2

b2_center_y = (b2_y1 + b2_y2) / 2

center_distance = (b1_center_x - b2_center_x) ** 2 + (b1_center_y - b2_center_y) ** 2

enclose_x1 = torch.min(b1_x1, b2_x1)

enclose_y1 = torch.min(b1_y1, b2_y1)

enclose_x2 = torch.max(b1_x2, b2_x2)

enclose_y2 = torch.max(b1_y2, b2_y2)

enclose_diagonal = (enclose_x2 - enclose_x1) ** 2 + (enclose_y2 - enclose_y1) ** 2

b1_w, b1_h = b1_x2 - b1_x1, b1_y2 - b1_y1

b2_w, b2_h = b2_x2 - b2_x1, b2_y2 - b2_y1

aspect_ratio = 4 / (torch.pi ** 2) * torch.pow(torch.atan(b1_w / (b1_h + eps)) - torch.atan(b2_w / (b2_h + eps)), 2)

v = aspect_ratio / (1 - iou + aspect_ratio + eps)

ciou = iou - (center_distance / (enclose_diagonal + eps) + v)

return ciou

class CIoULoss(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super(CIoULoss, self).__init__()

def forward(

self,

preds: torch.Tensor,

targets: torch.Tensor

) -> torch.Tensor:

ciou = bbox_ciou(preds, targets)

loss = 1 - ciou

return loss.mean()

The CIoULoss is just a handy wrapper for the function calls, nothing magical here. However, the last line is worth noting. The loss.mean() call turns the losses tensor into a scalar value (the loss variable is a tensor of the losses of all the bounding boxes for the given batch). I could have used the loss.sum() reduction, so why didn’t I? It’s quite simple if you think about it for a while. If the batch size changes, the mean calculation will always return numbers on a similar scale, while the sum calculation will be strongly tied to it - bigger batch size equals a bigger number. While experimenting to find the right batch size, it’s easier to compare similarly scaled loss values. Additionally, when summing, larger batches produce larger gradients, which means the training may become unstable.

Although I try to avoid including too much math in my ML/AI efforts, sometimes it’s unavoidable. Seeing the above blob of code in 3 months, I might not remember what it does, so this mathematical formulation can be helpful:

Starting from the top:

-

IoU calculation consists of dividing the Intersection Area (the area of the overlap between the actual and predicted bounding boxes) by the Union Area (the total area covered by the actual and predicted box minus the intersection area). These two are what constitute the IoU metric. If the predicted bounding box and the ground truth bounding box overlap, this metric will give a value closer to 1; otherwise, it will be closer to 0. The CIoU metric adds two more factors: the centers of the predicted bounding boxes and their aspect ratios. The purpose is to offer richer gradient information, which may help the neural network converge faster.

-

CIoU calculation subtracts the sum of the squared Euclidean distance between the center points of the predicted and ground truth boxes (normalized by the squared diagonal length of the smallest enclosing box that can cover both the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes) and the aspect ratio from the IoU result. That’s a long sentence with many details, so let’s see the next equations.

-

This term penalizes the distance between the centers of the two bounding boxes. The numbers are squared to avoid non-negativity and penalize larger distances. This way, the model is trained to correct larger errors more aggressively.

- This term is used to normalize the Euclidean distance calculation result (that comes from step no.4). It’s the squared diagonal length of the box enclosing the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes. If you divide the center distance by it, you’ll get a value that lies inside the interval of \([0, 1)\). It won’t ever really reach 1 because the corners of the enclosing box will always be at at least slightly different coordinates than the centers of the bounding boxes. This normalization helps with:

- Numerical Stability: Ensures that the loss values do not become excessively large, maintaining a stable range of values.

- Proportional Penalty: Adjusts the penalty for center misalignment relative to the size of the bounding boxes, ensuring fairness across different scales.

- Balanced Loss Components: Prevents any single component of the loss from dominating, leading to a more balanced and effective optimization process.

- Consistent Gradients: Facilitates stable and consistent gradient updates, improving the convergence and performance of the model.

-

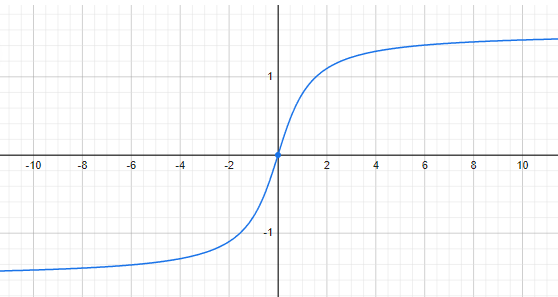

The parameters \(w\), \(h\), \(w^g\), and \(h^g\) represent the width and height of the predicted bounding box, and the width and height of the ground truth bounding box, respectively. By dividing widths by heights, an aspect ratio is obtained. This aspect ratio needs to be constrained to an interval to prevent it from dominating the entire equation. This is where the arctan function comes in.

The arctan function outputs values from \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) to \(-\frac{\pi}{2}\). The maximum difference between two arctan values is \(\pi\). Multiplying \(\frac{4}{\pi^2}\) by \(\pi^2\) (the maximum result that can be obtained within the brackets) yields the number 4. If you’re wondering why this particular number is used, I must admit that I don’t know. I couldn’t find any explanation on the internet for the choice of 4 instead of, say, 1. My best guess is that since this constrains the equation result to the interval \([0, 4)\) , it allows the aspect ratio term to be weighted as more important (4 times more important) than the previous term. - The last term is what makes CIoU look very smart to me. If the IoU result is close to 1 (which means a good overlap between the predicted box and the ground truth box), the \(1-\text{IoU}\) term will cancel out resulting in \(\frac{v}{v}\) which is equal to 1. This means that in the case of a good overlap, the aspect ratio term will be weighted higher, and from that point on, the loss function will try to optimize for it. Conversely, if the overlap is not that good, the \(\alpha\) term will be a small number, weighing the aspect ratio lower, thus allowing the loss function to promote finding a good overlap first.

Summary and next steps

The history of machine learning and AI shows that so-called smart solutions don’t always work. In my eyes, the CIoU loss function is one such solution, but it seems to have been used with good success in computer vision. Seeing how elegant this function is, I would really like for it to be successful in solving the problem at hand with the best results. To that end, the next article will contain a comparison.